Inspiration - A Blog Series by Dr. Michael S. Heiser

This is going to be a LONG post. The Biblical scholar I read/listen to most often is Dr. Michael S. Heiser. Mike has a blog series on Inspiration which was originally written in 2008 and was linked here:

However, some of the links on that page are broken and you have to search the site separately to find the posts (and at least one of them doesn’t exist). Additionally, there are 24 separate posts that are intended to be read in order. Frankly, it’s a bit unwieldy to try and read it all (particularly since some of the links are broken). So I decided to repost it all as one blog post below. I’ve included links to each of the individual blog posts at the end of each of the posts. That will allow you to review the comments at the bottom of each post and better understand how things developed. I hope you find this interesting and useful - it’s a good example of a scholar working through some ideas… asking for, considering, and using input from lay people and another scholar… and coming to a more refined position. I could not find the original first post anywhere (even with Wayback Machine), so the first post below is actually the second post. On to the series!

Looking at the Inerrancy Definitions, Part 1

Let me say at the outset that I personally have no problem with the word “inerrancy” and want to embrace such a doctrine as an evangelical. My problem is that I’m not sure how to articulate what the word should mean so that it’s honest, defensible, and coherent. I believe truth corresponds to reality (correspondence view of truth), and so I can’t make up a definition that does not correspond to reality and then pretend it works (and worse, is self-evident). My goal is therefore not to undermine the idea of inerrancy, but to come up with a definition (or even a lengthy explanation) of the idea that honors the data of the text and the world around us, for which God is also responsible (general revelation). We can’t look away from the phenomena of Scripture–what’s written is what’s written, and it’s what God intended to be written (yes, I distinguish the autographs from copies)–nor the phenomena of general revelation (if the Bible said “pigs can fly” it would be in error). Now some brief “first thoughts” about the definitions:

1. Grudem’s definition: It’s simply inadequate. On one hand, it doesn’t offer the sorts of qualifiers the others do in a succinct way (though Grudem eventually gets to some of that discussion); on the other hand, those who lack any experience spent on this issue would be led to believe the issue is far simpler than it is. Grudem knows the issues, so I’m not sure why he settled on this definition.

2. Two of the articles I asked you to read are very clear illustrations of the pre-scientific worldview of the Bible. Erickson and Reymond have language in their definitions that seem to allow for this (without using the word “pre-scientific” or “unscientific”), but they also talk about the Bible not erring in what it “affirms.” There is nothing in their definitions that informs us what is meant by “affirm,” though they do insist that the Bible be taken on its own terms (and I’d agree there). A key issue will be what is meant by “affirm.”

3. Reymond wrote: “we must not evaluate Scripture according to standards of truth and error that are alien to its Sitz im Leben . . . .” I like that, but do we mean it? What if that means the biblical authors believed there was a solid dome over the round, flat earth? I personally don’t think we should judge them for that–that was their worldview. Why would we expect anything else? Here’s the real issue, though (for these definitions): is this pre-scientific worldview “affirmed” by the biblical author? Is it “assumed” — and is that any different than “affirmed”? Does it even matter — maybe the “affirming” language has to go, to yield to something better. That’s what I want us to think about.

4. Reymond’s discussion also includes the qualification about “the use of hyperbole and round numbers.” Fair enough–but what if the use of such hyperbole is a literary feature and completely deliberate (a deliberate exaggeration)? I have a friend who did his dissertation on large numbers in the OT, and reached the (quite coherent) conclusion, based on comparative ANE historioraphic accounts, that exaggeration of numbers was a stick element in such literature (you were supposed to brag up your god). Is this “affirmation” of deliberate disinformation? Is there a better way to view this?

5. I think the issues in numbers 3 and 4 need to be viewed in light of Erickson’s note about “the purpose to which Scripture was written.” Purpose can dictate both literary technique and is not thwarted by pre-scientific worldview. The author’s audience could not process anything by their own worldview, and has certain expectations about how something should be written to accomplish an intended purpose. In other words, there is nothing deceptive going on. Yes, the biblical author can be scientifically ignorant and still get his point across–the purpose isn’t impeded. But is ignorance of some now-known scientific fact to be equated with “affirming” that ignorance as truth?

6. I’m on Peter Enns’ side, but I find his definition unsatisfying. It just doesn’t deal with any of the issues (and doesn’t pretend to want to). Someone who is struggling with the phenomena of Scripture isn’t going to find any help there.

Looking at the Inerrancy Definitions - Part 1

Pre-Scientific Worldview “Problem” and Inerrancy

Taking off on Chet’s lengthy response [in a comment] to my “Definitions of Inerrancy” post:

The first thing I’d like to pursue is Chet’s criticism of the word “affirm” — I also think it’s a weasel-word. You quote 1 Cor. 11:14, which says, “Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him?” Here Paul makes a specific statement about nature–it’s clearly a comment on the natural world and a truth that Paul believes the natural world communicates or points to. Having read the article in the readings list, it is quite clear that Paul’s statement is rooted in an absolutely non-scientific worldview. His statement is scientifically false. I’d say he’s clearly “affirming” something about nature here and then extrapolating to his more significant point. So, I think we need to dump this “affirming” language as some sort of safeguard (read: weasel-word) for defending inerrancy. Here’s what I’d like your (and others’) thoughts on:

1. Paul is clearly in error in terms of his understanding of nature on this point (he’s a pre-scientific man). Does that matter? Although Paul believed this, is he putting forth this belief as something his readers must believe? That is, while his contemporary readers no doubt believed what he believed, should be view this belief as something that we must believe? Is this the way this statement is cast? Put another way, when I read this passage, is Paul’s belief about hair what I am supposed to embrace as truth from this passage? I don’t think so, and I think you’d agree. But I also think it would be silly to say Paul isn’t “affirming” the particular erroneous belief about hair. He believes it.

2. Should we give Paul a pass? I’d say, of course — how is he supposed to know anything else? The science of his day was primitive by our standards.

3. What ARE we supposed to embrace from the passage? What is Paul teaching? I don’t think he’s teaching us about biology or sexual reproduction–though he presupposes some beliefs about those things that are erroneous when making his argument. If he’d said “this is what God wants you to believe about how we get babies,” the inerrancy issue would be a dead one-inerrancy would be untenable. But is it coherent to say that a speaker or writer’s conclusion or position cannot be correct if his arguments are not always correct? Obviously, the answer to this is no. People are right about X all the time when their reasons for thinking they are right are bogus. We all know that. But in this passage of Scripture this leaves us with a problem: How are we to correctly discern WHAT Paul’s point is (the thing that can still be correct) if the argument he’s using is wrong? That’s a problem, but I think it’s not an issue of inerrancy so much (as stated) as it is an issue of interpretation.

I say all the above to say this: perhaps in our understanding and articulation of inerrancy we should make it clear that taking the Bible on its own terms means not expecting more from the culture that produced it than is fair. I don’t think it’s fair for us to judge Scripture by standards foreign to the people who produced it. God chose to come to people of a particular culture, a particular region of the world, at a particular time. He used what he had at his disposal once he made that decision-some people who didn’t know squat about a whole host of things (and we’d have to say that about ourselves were we the people God chose to communicate through). God wasn’t trying to teach us science in the Bible precisely because he wasn’t teaching its authors science. They wouldn’t have understood it, and even if correct science was dictated to them, their readers wouldn’t have understood it. That would sort of defeat the purpose of dispensing revelation, wouldn’t it? (“I’m going down there and telling them lots of things they can’t grasp-and then hold them accountable for it” Huh?). To use the weasel-word, I’d say the Bible specifically does NOT “affirm” anything about science because God didn’t have anyone at his disposal sufficient to the task. So, I don’t care if Paul is wrong in his science; God didn’t care either.

But while Paul’s science shouldn’t be embraced by us as truth, can’t we still embrace what he says in this passage outside of science? I don’t think the hermeneutical gap in this instance (1 Cor 11) is that wide, either. I think we can get a pretty good idea of what Paul meant, however odd or wrong his reasoning process was. I’d say we CAN discern the truth item God wanted him to communicate while allowing Paul (even directing Paul) to make that point on the basis of his worldview’s bad science. The original audience wouldn’t have been able to understand it any other way. Our task is to recover his worldview and THEN judge the ends to which he’s arguing, not necessarily the means.

So, I just don’t think the pre-scientific worldview issue forces me to not hold to inerrancy. It DOES force me to not word what I believe the way the earlier definitions are worded (at least with respect to the “affirm” wording). I’d like to do better.

Not sure this helps (me or anyone else).

Pre-Scientific Worldview “Problem” and Inerrancy

A Short Explanatory Note on the “Westminster Addendum”

Just a quick clarification on what is meant by the “Westminster Addendum” in my last post. The “addendum” refers Primarily to a statement made by Westminster Seminary, not the Westminster Confession (but see below). The seminary, in suspending Peter Enns in regard to his book, Inspiration and Incarnation, posted a lengthy PDF document on the seminary’s website in an effort to explain their decision. On page 7 of that document we read this paragraph:

'For the Reformed, God was the author of Scripture, and men were the ministers, used by God, to write God’s words down. Scripture’s author is God, who uses “actuaries” or “tabularies” to write His words, who are themselves instrumental secondary authors. Reformed thought has been careful to see God as the primary author, and men as instrumental secondary authors. And, if instruments, then what men write down is as much God’s own words as if He had written it down without human mediation (a point that will be mentioned below with respect to Kuyper’s discussion of an Incarnational analogy). So, WCF I/4 notes that Scripture’s author is God, not God and man. “The authority of the Holy Scripture, for which it ought to be believed, and obeyed, dependeth not upon the testimony of any man, or Church; but wholly upon God (who is truth itself) the author thereof…” This notion of divine authorship is in keeping with the Scripture’s notion of itself, i.e., that it is theopneustos (“God-breathed,” 2 Tim 3:16); it is not theo- and anthropopneustos.'

I find this approach very unhelpful and puzzling. Some might even call it nonsensical in that those who engage the biblical text closely know, for example, that (1) the gospels use different wordings (frequently); (2) the NT writers change the wording of OT quotations and/or opt for translations (LXX) of OT verses when quoting them (and the translations themselves at time alter the original Hebrew wording); (3) later parts of Isaiah use earlier parts of Isaiah an apply them to different historical circumstances (and I am not one that accepts the “traditional” view of multiple Isaiahs). If the writers wrote as God would have written himself (and one wonders why God did not just do that in incarnated from if that was the point), then why these very obvious differences and practices? It’s an honest, straightforward question that this paragraph does not account for in any coherent way. Hence I feel the need, as one who affirms inerrancy, to do better than Westminster Confession or the Chicago Statement in how we articulate the idea. And this is far from the only issue that needs to be addressed, as readers well know. OT and NT writers also use a panoply of literary conventions (like treaty arrangements; epistolary formulae, etc.) used widely in the ancient world; etc. Why these human choices in the process? Why do we have transparent agendas on the part of the Chronicler, for example? I guess the better question is, Why is any of this a problem? God uses people (surprise) to do his work and will. We believe that “God was in the process” with canonicity, and articulate that doctrine with Providence as a specific part of the recipe – why not inspiration?

A Short Explanatory Note on the Westminster Addendum

Sifting the Posts and Comments on Inerrancy

I thought it might be helpful to direct our attention to some specific thoughts / items that have appeared in posts or (mostly) comments. I’ve reproduced a dozen below. These thoughts seem to me to be fundamental to beginning a problem-solving path or paths.

1. To what extent does the worldview of the Biblical authors affects the accuracy and understanding of the text?

2. I believe that inspiration is a PROCESS, not an event.

3. Personally, for me the issue is becoming how to answer the question, “What information did God want us to have – what was the point of the exercise?” That is, I think we need to focus on the inerrancy of the ENDS to which God did what he did in dispensing revelation, recognizing the imperfection of the MEANS.

4. Let us imagine Jesus saying, “As it was in the days of Prince John, etc”? Must we then believe that Robin Hood in fact split the shaft of an arrow?

5. As an interpretational stance, we must imagine everything happening just the way the narrative says, because that’s what it invites us to do. Beyond that, though, the epistemological ground gets very soft very quickly.

6. We can (should?) extend Jesus the same courtesy we do Paul – he says whatever he deems necessary in order to communicate his message in a way that his hearers can understand.

7. But can we not assume that Jesus is capable of condescension? In fact, being peerless, Jesus must condescend in order to communicate at all. Or if you like: The communication occurs at grasshopper-level, and Paul is already down in the lawn with the rest of us, where Jesus is not. Whether or not Jesus knows better as a matter of fact is beside the point; He must still communicate to his audience on their level, not from his.

8. In any case, if we “affirm” verbal plenary inspiration, then surely we must hold God the Holy Spirit as he carries Paul along to the same standard as God the Son when he speaks? Or does the Holy Spirit get a pass but the Son does not? Is it because the Holy Spirit, operating under the aegis of a mortal, can thereby shield God from error, where Jesus, speaking under his own aegis and revealing the Father in word and deed, cannot?

9. That is, Jesus is not the author of Matthew 24:37, Matthew is. (Let that percolate for a while.). We glibly say that “Jesus says X” when saying “Matthew says that Jesus said X” would be more accurate.

10. Any doctrine of inspiration that tries to write the human authors out of the picture is hopelessly impoverished.

11. If humans are involved, the process is human (!), but that doesn’t mean it’s ONLY human. The reverse is also true. IF God is involved in the process, it’s a divine process, but that doesn’t mean human agency isn’t involved. The “addendum” seems to deny any genuine human input or decisions resulted from this process (the “all of God” idea). I think that’s a bogus position and antithetical to Scripture, much less the reality of the text as we have it (and as God preserved it).

12. We have the providentially preserved, inspired text before us, produced by a process whereby God used imperfect humans to write. I believe that the result of it should be called inspired and inerrant, but current explanations of these terms don’t help resolve the “messiness” – but that doesn’t mean we are left with errancy. It means (to me) we need to do better.

As I noted in one of my recent comments, once the dictation theory is dispensed with, we are not left with “God alone” authorship. God can still supervise a human process without dictation. The problem before us is how do we deal with the “messiness” that is the result of that process? How do we frame things like the pre-scientific worldview issue, the “misquotations,” authorial bias (Chronicler), the secondary nature of the gospels and all the historical narratives – the reality that no one preserved the exact dialogue through taping it, so to some extent dialogue is “made up” (better, recalled imperfectly; Ivan: “We glibly say that “Jesus says X” when saying “Matthew says that Jesus said X” would be more accurate”). I think these things (and a panoply of others) can be allowed to be what they are and not impinge on inspiration and inerrancy. But HOW TO SAY THAT? HOW TO DEFINE THE DOCTRINES so as to be honest with the data of the text?

Sifting the Posts and Comments on Inerrancy

Parsing the “God Alone” View of Inspiration

I’ve tried to put forth what I think is the standard “only God is responsible for the Bible” view reflected in the Westminster addendum quotation (the theopneustos, not anthropopneustos one reproduced in two posts already). I’ve noted a few questions in the course of this as well. I may not be getting it right, but here goes:

I think we can all accept the idea of God making sure the results were what he wanted, but may disagree on the extent of God’s oversight. I think the fundamental difference I’d have with the lefthand column is that I’d allow real human freedom in making the word choices and literary features, etc. (that sort of thing). I’d still like my “ditto” questions answered, since we can’t have humans getting any credit for any of the content in the Westminsterian view – which of course means that humans shouldn’t get any blame for when the received content is discussed when we drift into INERRANCY. God either put each word into place ALONE or he didn’t – you can’t have God acting “mostly alone” or “alone but with someone else doing it.

Now an important point: I’m hoping readers see how the above table as it is really only deals with INSPIRATION and not INERRANCY. The former is fairly easy (“God did it this way” – and one would wonder why mode is so mysterious in this view; it seems a mystery only if you desire to keep humans from getting any credit or making any choices that weren’t already chosen). At any rate, now that we “know” what God did, how do we assess the truth or veracity of the content (INERRANCY)? This is really where I intended the discussion to focus when I started it. We have drifted a bit into inspiration and away from inerrancy, but not without good reason. How should we articulate the realia going on in the text as to its “truth status”? I agree with the Chicago Statement (and have said so in past posts; paraphrasing here) – that it’s wrong to judge the content by standards unintended by the purpose of inspiration, so how do we tackle this in a statement or series of statements?

Looks like we’re back to weasel-words like “affirm” – or, better, my previous post pulling out some of the blog’s more important (in my view) ideas that (I hope) can help in this area.

For me, my mind right now wants to start with “what was the point of the exercise (of inspiration)?” But feel free to pick up another item from the list in the last post, or continue here with my questions in the table. I could live without getting an explanation as to how the lefthand column view is NOT dictation, since I’d give the author’s more freedom (but then they get some credit for making choices – which would seem to be anthropopneustos, or whatever that word was). Maybe there’s a way to give them more freedom and not have them get undue credit.

Please, chime in! I need some wordsmiths and thinkers! None of this is designed to provoke. Where else am I supposed to go but to readers who share the same interest in the questions? Short of inviting you all over for burgers, this is what I can do.

Parsing the "God Alone" View of Inspiration

The Naked Bible’s Thoughts on Inspiration, Part 1

I’ve reached a point with this subject where I think it’s time to just start putting out what I think about inspiration and inerrancy. It’ll probably take a few posts on the former before I get to the latter. Your comments have been helpful, but I’m sensing that I could be clearer. I’m going to lay out how I think inspiration worked and, in the process, try to clarify where my thoughts diverge (at least in my mind) from the Chicago Statement and other formulations. This way you’ll see how I’m thinking about all this.

Let’s start with 2 Timothy 3:16. I’ve gotten more than one comment quoting this passage to me like it settles the issue. It doesn’t. In fact, it invites questions. Yes, I believe that “All Scripture is inspired (Greek: theopneustos) by God and is profitable …” I take theopneustos as a predicate adjective, not attributive (which would read, “all God-inspired Scripture is profitable …” suggesting some Scripture isn’t God-inspired). Since I don’t accept the attributive adjective here, I’m not in the limited inerrancy camp.1

All well and good – but what does “inspired by God” (theopneustos) mean? Well, Mike, it means God is the source of the Scriptures. That’s nice, but the point of the term is not self evident. We have to make a choice about theopneustos. We could say one of two things about the term’s meaning:

1. The term theopneustos refers to the IMMEDIATE source of the Scriptures – and so we have God breathing out the Scriptures directly to the writers. How did he do that? Did it happen as some sort of audible “whisper in the ear,” or did God implant each word into the head / mind of the author? The former is quite clearly dictation. The latter is very close to that — Is there a difference between aural and mental dictation? Whether you want to call it dictation or not, you have God PROVIDING each word; he is the immediate source of each word. This is probably where most evangelicals are in their understanding of inspiration. This view not only takes theopneustos as meaning God provided each word as the immediate source of all the words, but it also requires that humans aren’t the immediate source of any of the words (remember the Westminster Addendum’s firm denial of anthropopneustos). But humans have to have some sort of role (no one denies the Scripture was *written* or that God was literally holding the pen as it were). This is where the notion that humans are “secondary sources” of inspiration comes in. So, to summarize, God is the immediate and primary source of inspiration, and humans are secondary sources. None of the words of the text ORIGINATED with humans. But again, if we are saying that none of the words of Scripture originated in the mind of a human author, how does this escape some sort of dictation or automatic writing (where the human agent goes into a trance state and is taken over by an outside invisible force that writes for him / her)? What I want to see is an explanation of how this understanding simultaneously avoids both of these dictation options and still has no words ORIGINATING with the human authors. Good luck.

Better, why not opt for the second way of looking at theopneustos, which makes much more sense (at least to me).

2. The term theopneustos refers to the ULTIMATE source of the Scriptures – and so we have God as the ultimate point of origin for the Scriptures and humans as the immediate source of the Scriptures. If you are following, you can seen that this view acknowledges “anthropopneustos” in the sense that the human writers made decisions about what they wrote and so the Scriptures ORIGINATED with humans, albeit at all times under the aegis of the ultimate source, God. Naturally, God could choose to encounter the writer directly, which he RARELY does in the Bible in contexts where he instructs his words to be directly recorded. But this is not the norm. The norm is that humans produce the words of Scripture under divine supervision. This is easy to illustrate.

We are fond of saying that God is the source of ALL life. I agree-but I would qualify that by saying that he is the ULTIMATE source of all life, and not the IMMEDIATE source of life. For example, humans make babies (lots of them). Each baby is not (sorry moms) an individual ex nihilo act of creation by God. Babies are born via sexual reproduction. When the human organism functions as God made it to function and couples have sex, babies are the normal result. And so, humans are the immediate creators of the baby and thus of that human life. However, God is the ultimate source of that human life, since God made and animated the first human beings and created them with a means to reproduce. No human being would exist without the first act by the Maker, who is God.

Another analogy: we create things all the time, say, cell phones. The cell phone in your purse or on your belt was not called into existence by God, even (especially!) if it’s an I-Phone. Rather, humankind was commanded by God (the dominion mandate) to discover and master what made the created world tick and equipped them accordingly for that task. That knowledge has now progressed to the point where human beings can now make cell phones. But it is God who made all the elements of which cell phones are made, and so no cell phone would exist without God’s act of creation of the elements. God is thus the ultimate creator of cell phones, but not the immediate creator. We could say cell phones are “breathed out” by God in an ultimate sense, but not in an immediate sense.

So were the Scriptures. If we take theopneustos as referring to God as the ultimate source of Scripture, the dictation / automatic writing problem disappears. Humans become the immediate source that produced the text via their own abilities and decisions (like they are the immediate source of babies). God is the ultimate source in that (1) he created humans, (2) it was his idea to give us revelation; (3) he hand-picked the people and created the circumstances that gave rise to the Scriptures. Now some logical questions or statements that I’m sure are in the mind of some:

o So how was God only the ultimate source of the Scriptures – how does he “get involved” with humans writing in a way that avoids the dictation problems of the other view?

o It bothers me that you say the words of the Scripture originated with humans under the auspices of God. It doesn’t seem like God gets enough credit.

o Did God preserve the humans from error? Wouldn’t such preservation require the first view – that we have to have extremely close supervision of every word (almost dictation)? How can you have God preserving the originators of the words from error without becoming the originator of the words?

I hope you see from these statements why I argued earlier that we need to model our view of inspiration after the typical (Westminsterian!) view of canonicity. In canonicity, we don’t have God audibly telling leaders which books were in or out. We have humans making those decisions, being guided by divine providence in those decisions. In other words, we say God was in the process; we trust providence.

Ditto to the three questions / objections above.

If God can providentially oversee the process of canonicity through the Spirit working in the believing community without it involving some direct divine visitation, he can do the same in inspiration. How big is your God? He’s up to one task and not the other? Preservation from error in the process gets done however God operates in providence (which operations are myriad). God is involved however he wants to be. He COULD speak to a writer directly (the Scripture itself shows us this is rare), or he could mold a person through a series of life events that lead him to write something, then watch, step back and say “Not bad, Paul; that’ll do,” or “John’s not as good a writer as Luke, but he got the job done. Maybe I’ll let him write something else …”

The point is that God is not required to pick every word himself in supernatural visitation for the end result to be satisfactory to him – precisely because he can intervene in a very human process whenever and however he wishes to prevent human frailty from undermining his intentions. Again, I ask, how big is your God? Can he only work by direct proximity? Is he spatially challenged? No. If you need God to originate every word, thereby reading INTO theopneustos a view that mandates no word can originate with humans, then I think your God is too small. Or, to quote Ivan (the Terrible Postmodern): “Any doctrine of inspiration that tries to write the human authors out of the picture is hopelessly impoverished.”

Next post: II Peter 1:20-21

The Naked Bible's Thoughts on Inspiration - Part 1

The Naked Bible’s Thoughts on Inspiration, Part 2

In this post I want to turn to 2 Peter 1:20-21 and share a few thoughts on how this passage dovetails with my views on 2 Tim 3:16. Here’s the passage (ESV):

20 knowing this first of all, that no prophecy of Scripture comes from someone’s own interpretation. 21 For no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.

I’m with the majority (I suspect) that would argue that “prophecy” here refers to any sort of utterance from a prophetic (or apostolic) figure that wound up getting recorded in Scripture. (Though the passage says “spoke” it can be applied to the production of Scripture since what was spoken was often written or written about). No argument there. The passage makes it clear that no part of the Scripture was produced ONLY of human origin. No argument there, either, as readers will know. In my post on 2 Tim 3:16, I argued that the immediate source of Scripture was the human writers, while the ultimate source was God. I also argued that the former could not exist or function without the latter. The divine element, though not immediate, is primary.

I think the issue for some in this text might be that some would imagine Peter’s statement that “men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” to be in conflict with my position. It doesn’t, and I hope I can clearly explain why.

Those who don’t take my view would likely argue that Peter’s statement looks a lot like total control of the authors by the Spirit in producing the Scripture. They might like the standard proof-text for this idea obtained by searching for the lemma behind “carried” (φερω): Acts 27:15, 17. In Acts 27, the ship in which Paul, his fellow prisoners, and their captors was on was said to have been “driven” (φερω) by the wind in these two verses. It is argued by extension that, as the ship was totally controlled by the wind and moved wherever it blew, so the human authors were totally controlled by the Spirit. For those like the authors of the Westminster (seminary) addendum, who want to deny human decision in authorship and word choice (they deny anthropopneustos), this description would apparently suggest that the human authors were incapacitated by the Spirit in some way so that what they produced was only theopneustos and in no sense anthropopneustos. Remember, in that view, the Scriptures can originate ONLY from God.

This is fallacious reasoning that uses selective reference to the lexicon to prop itself up.

The analogy between the ship and the human writers is flawed. There are little incongruities, like the fact that a ship doesn’t have a brain, a will, or self awareness. Then there is the recurring problem of how a total overtaking of the authors is not to be equated with either a dictation view of Scripture’s origin, or an automatic writing view. The description sounds a lot like automatic writing to me, where the author is overtaken by an entity (in this case the Holy Spirit) so that what he writes is not his own, but is only reflective of the mind and will of the controlling agent. It is as though the author’s mind goes blank, or perhaps doesn’t go blank but is utterly controlled by the agent, so that not a single word of what is produced can be attributed to the human being. Remember, we must deny anthropopneustos in this view. Now, while I think the X-Files was the television event of my lifetime, I don’t want Fox Mulder doing my NT exegesis. This sounds a lot like something he would suggest. It would be very easy for me to note the use of φερω in Mark 15:22 where the object of the verb is Jesus: “And they brought him to the place called Golgotha (which means Place of a Skull).” I don’t think we want to argue that Jesus was “driven” by ONLY his captors to the cross. No, he was there by the will of his Father and his own decision to submit to the Father. (We’ll see more examples below of how φερω should not be construed as utter control).

I believe 2 Peter 1:20-21 clearly gives us both elements of inspiration, the human and the divine. I would argue that, like 2 Tim 3:16, this passage lets us know that the human element was not exclusive or primary but does not deny the human element. 2 Peter 1:20-21 does not suggest the human element was not real, nor does it assert that the human element had nothing to do with the results. The divine does not erase the human or make the human unnecessary. In reality, if the dictation or automatic writing view were the truth, it is that view which would indeed make the human element superfluous, save that the Spirit needed a body to use (which is the essence of automatic writing). No, God could have become embodied to directly dictate (“man to man” as it were) or to write himself. He didn’t choose either.

Let’s talk a little bit more about the verb φερω. When it is used where one intelligent being with will and self-awareness (the subject) is acting upon another intelligent being with will and self-awareness (the object), the subject’s action does not nullify, erase, or otherwise obliterate the intelligence, will, and self awareness of the object. Some cases in point:

Mark 1:32 – That evening at sundown they brought (φερω) to him all who were sick or oppressed by demons.

Mark 7:32 – And they brought to him a man who was deaf and had a speech impediment, and they begged him to lay his hand on him.

Are we to conclude that φερω “by definition” is to be understood as it is used in Acts 27:15, 17 of the mindless, lifeless ship? Did people have to compel the blind, lame, and deaf to go see Jesus so they could be healed? Were all these incidents situations where the will of the object had to be subdued so the object became passive? This reasoning is, of course, silly. And I’d add that arguing that this verb ITSELF rules out all other external decision-making capabilities of the prophetic figures in 2 Peter 1:20-21 because of the analogy of the ship in Acts 27:15, 17 is plain old sophistry. We don’t need to play such games.

So how do I understand “carried along” (φερω) here? The same way I understand it in the above examples: assistance. As I expressed in my previous post, “God was in the process” any way he desired to be, and by any means. I don’t rule out direct influence, such as a supernatural appearance to a writer, but if and when such instances happened, they didn’t make God the immediate source of the Scriptures as a whole (or even at all). If we take a larger, providential view of the Spirit’s assistance to the writers, that could occur via the Spirit creating the circumstances for a particular conversation to occur, where the writer was influenced in some way to write something. It could mean bringing a source of information to a writer (a person or book). It might mean that the Spirit used the Old Testament itself to move a writer to write something. The means were varied and broad. The end was that Scripture was the product of human writers assisted by the Spirit. The divine element doesn’t lose credit in this view; it actually becomes bigger and more far-reaching in the way it plays out.

There is simply no need to divorce the product of the process from human authors. So why do so many want it that way?

The Naked Bible's Thoughts on Inspiration - Part 2

The Naked Bible’s Thoughts on Inspiration, Part 3 – The Myth of the Holy Stapler

In the previous two posts I’ve laid out my thoughts on the relationship of the human writers to God’s role in producing the Scriptures. I have argued that it is flawed thinking to deny that Scripture originated with humans in ANY sense; that is, anthropopneustos is neither denied by 2 Tim 3:16 nor 2 Peter 1:20-21. Human beings are the immediate source of Scripture, but God is the ultimate source. I have sketched out a view of inspiration that is modeled after the “normal” orthodox view of canonicity: God was in the process and by a range of providential means, he saw to it that human agents produced a canon that He endorsed and with which He was satisfied. The thing human writes produced got God’s seal of approval since He oversaw their work by providence, not by dictation or seizing the minds, limbs, and hands of the writers.

Today I want to bring something into the discussion that has heretofore not been dealt with: the matter of how the Bible was edited. The Bible itself bears testimony to editing, and the manuscript evidence left to us by providence makes it clear that editing of the canonical books occurred. I can’t recall any (conservative) evangelical theology books that really deal with this in their discussions of inspiration. If anyone knows of one out there, let me know. One of the few conservative scholars I know of who has touched this issue at all is Mike Grisanti of Masters Seminary. I won’t be going through his JETS article, but you can download it if you want to give it a read. I will, though, lift a few examples from it, while adding my own. Let’s start first by dispensing with the common mythical view of how the biblical books were created.

I’ve spent a good deal of time discussing the dilemma of the traditional view. On one hand, every effort is made to deny that inspiration was dictation and to affirm human input. But on the heels of such statements, some evangelicals (and I have targeted Westminster seminary’s recent statement on this issue) turn around and say that ONLY God should be considered as having produced the Scriptures. Theopneustos is to be affirmed and anthropopneustos is to be denied. And so we have the dilemma. I put the question this way: Is there a coherent explanation of how God did not dictate the Scriptures or seize the mind of the human author, but where the words are produced only by God so that the human writers are in no to be viewed as the source of the writing that was produced? Put another way, How can you deny anthropopneustos, that humans are responsible for what is produced, while at the same time avoiding both dictation and automatic writing?

A corollary to the view that humans are not responsible in any way for what is produced by the process of inspiration is that the biblical books as we have them today were produced by single writers in one attempt. That is, when Moses or Luke or Matthew or Paul sat down to write what they wrote, they did it and it was never touched again by them subsequent to the “inspiration event” – and especially not touched by someone whose identity is unknown in the Scriptures. It seems that we cannot have nameless scribes living decades later touch the initial product of the prophet or apostle and edit it in any means, since that (presumably) would be a denial of inspiration.

These ideas fail to view inspiration as a PROCESS, rather than an event. There was no “event” of inspiration with respect to an entire book. Yes, there were divine encounters, and on rare occasions those resulted in written material, but that material was actually only part of a bigger book. Inspired books, though, were not the product of an event or a series of supernatural encounters. They were the result of a long process of successive providences and hard work on the part of the human writers. Here’s how most conservative evangelicals seems to view inspiration (as event). Imagine with me, if you will, Isaiah getting up for breakfast. His alarm clock goes off, he rolls out of bed, brushes his teeth, and goes to the kitchen for breakfast. He rustles up some eggs (hold the bacon and sausage) and toast and sits down to enjoy it. Suddenly he’s zapped by a bright light, his mind is seized and overtaken by God. He probably doesn’t hear God speaking (we must deny dictation, remember), but he knows the Spirit has overtaken him. In what seems like only a few moments, he comes to and voila! Before him lays a scroll filled with words. God has chosen him once again to be the conduit of revelation! The prophet Isaiah carefully rolls up the scroll and deposits it with the rest of the inspired material before the ark of the covenant. Then he goes back home and reheats his breakfast in the microwave.

Granted, this is silly, but it’s a basic overview of an inspiration “event” (might as well just say encounter and be done with it). Yep – in such a scenario there ain’t no anthropopneustos happening. Too bad this is fiction.

There’s another mythical view that affects how we view the creation of inspired books. We know it’s pretty rare (read the prophets) that God tells the prophets to write anything down. There are two ways (in the traditional perspective) for how we got their books: (1) To guess they went out a preached and then later were seized by divine encounter, the result of which was the same sermon they had just audibly delivered (but for which they cannot receive any credit), or (2) their followers (we know they had them) recorded what they said for posterity. In my experience, this second view is accepted, but gets a mythical twist that I like to call the myth of the holy stapler. Here’s what I mean in another dramatization. A few weeks after his dramatic inspiration encounter, one of Isaiah’s followers wakes up and gets ready for work. His job? Why, following Isaiah around and recording what he says. As he gets dressed he wonders if Isaiah will do anything weird today (helps make the day go faster) or if it’ll just be a normal sermon. He meets his colleagues (Isaiah is training other prophets like Elijah and Elisha – “the school of the prophets”) and they sit down and listen to the man of God. They each write as fast as they can, wishing they could have Isaiah repeat a few things, but they press on. They’ve been doing it for months (a few old timers have been there a couple years), so they’re pretty good at it. The next day they awaken to the shocking report: Isaiah has died! Now what do they do? Gripped by a sense of the need to preserve the prophet’s divinely-provoked sermons and teachings, they agree to get together and see what they’ve managed to record. One of them goes around the room and collects the notes of the others, stacks them neatly in a pile, shuffles them to make sure the edges line up, and then asks, “okay, where’s the stapler?” No one must touch Isaiah’s words since HE was the inspired prophet, not them, so all the notes get stapled together and so we got the book of Isaiah. Sorry, I just don’t believe in the holy stapler.

Again, this is ridiculous (but fun). Yet we seem to think that the biblical books just came together like magic. No, just like today, there was a way someone who wasn’t an idiot put together a book, especially something sacred. Judaism saw faithful, God-fearing scribes as part of the process of inspiration. It was their task to assemble the words of the prophet or craft the history of the kings, or assemble the psalms (etc.) so that the result was coherent, readable, and even a literary masterpiece. We like to pretend we know who wrote the biblical books, but the truth is that most of the authors are never named. Even when they are (like Isaiah), the actual contents of the book give little evidence that Isaiah himself was the writer. Rather, the material is frequently ABOUT the ministry of the named person and his preaching, and so the book is named after him. In the case of Isaiah, this is not to say the material isn’t Isaiah’s; it is rather to say that there are unnamed men behind the prophet who anonymously crafted his words into the book that now bears his name as part of a providentially-influenced process of inspiration. The same would be true of the other biblical books. God was in the process.

Now, I realize that the whole idea of editing may be unfamiliar to readers, and perhaps troublesome. If you hold to a view of inspiration something like what I’ve been sketching, it shouldn’t be troublesome. If you believe inspiration was a process, and model your view of inspiration after canonicity, and acknowledge that the Scriptures are the immediate product of people and the ultimate product of God through providence, this is no big deal. But for those who are still struggling with what I’m sketching, I want you to see that the Scriptures themselves give evidence of editorial activity. I’ll start with a few easy examples and in my next post, go through some more complex examples.

1. Deuteronomy 34:1-12 – Unless you believe that Moses wrote of his own death in the past tense (!), these verses were added to Deuteronomy, considered by conservative evangelicals to be the last of the books of Moses (the Pentateuch). See especially v. 6.

2. Genesis 14:14 – Notice the reference to “Dan” in this verse. Dan, of course, was one of the tribes of Israel. So what’s the problem? The tribe of Dan didn’t exist in the time frame of Genesis 14 (the period of Abraham). Now, one could suppose that Moses, who was contemporaneous with the tribes, wrote “Dan” when he wrote Genesis 14 during his own lifetime. That would take care of the problem were it not that this idea is denied by the Bible itself in Judges 18:29, which tell us that Israelites living AFTER Moses named the city Dan (“And they named the city Dan, after the name of Dan their ancestor, who was born to Israel; but the name of the city was Laish at the first”). The only coherent way to view this is that Moses wrote “Laish” originally in Gen 14:14, and the place name was later changed by an unnamed editor to “Dan” so people would know what place was being referred to.

3. The use of the phrase “unto this day” is often indicative of later editing.

A good example here is Deut 10:8 – “At that time the Lord set apart the tribe of Levi to carry the ark of the covenant of the Lord to stand before the Lord to minister to him and to bless in his name, to this day.” Again, if Moses wrote this, this rule was instituted in the Law he had also written. It makes little sense for Moses to say this was the rule “unto this day” since he was living at the time and had just written it (“Unto this day, Moses? No kidding – you’re still standing here”). It seems clear that a later editor wanted readers to know that in their (later) day, this rule was still to be observed. There are a lot of these kinds of passing comments in the OT.

4. Ezekiel 1:1-3

Pay close attention to the boldfaced items:

In the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as I was among the exiles by the Chebar canal, the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God. 2 On the fifth day of the month (it was the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin), 3 the word of the Lord came to Ezekiel the priest, the son of Buzi, in the land of the Chaldeans by the Chebar canal, and the hand of the Lord was upon him there.

Did you notice the shift from the first person (what we’d expect if Ezekiel was the author) to the third person? Who talks (or writes) this way? Who refers to himself in the third person (other than Rickey Henderson, for you baseball fans)? These verses read as though a scribe has taken some first person material written BY Ezekiel and then added a few lines (being careful not to put himself in the role of Ezekiel) to tell us what happened TO Ezekiel.

Again, this sort of thing happens a LOT. It is a clear sign of an editorial hand.

5. Psalm 72:20

This psalm reads, “The prayers of David, the son of Jesse, are ended.”

Really? Why then do we have a number of prayers of David after Psalm 72:20? Is this an error? No, it is an editorial comment by whoever put the books of the Psalms together. When he finished “Book 2” (Psalm 73 begins “Book 3”), the compiler thought they had collected them all. More were found later and put into the larger book. A verse like this, innocuous as it seems, can be real trouble for the “dictation but not dictation” view of inspiration I’ve been objecting to. If God is the ONLY source of the words of Scripture, you’d think he knew that all the prayers of David were NOT at an end! Seems a small thing for God to know, doesn’t it?

6. Isaiah 58:12; Isaiah 61:4; Isaiah 44:28; Isaiah 66:1

These verses and others refer to Jerusalem as being in a state of ruin and her temple needing to be rebuilt, conditions that would be obvious in the wake of the Babylonian captivity. But these references are in Isaiah, and the prophet Isaiah lived during the reigns of Ahaz and Hezekiah, in the 8th century BC, nearly 200 years before Jerusalem was taken. Some would argue that the first two verses are prophetic and written by Isaiah. Yes, the language can be taken as prophetic, but they would still be prophetic if written in the 6th century BC at the return from exile. The language doesn’t resolve the issue, and the other two verses are not worded as though prophetic utterances. Personally, I don’t think the two or three Isaiahs idea is the way to explain this kind of thing. I think it much more coherent to have editors adding such statements for the audience that emerged from exile. While there are clear evidences from the Hebrew (Hebrew changed through time, like any language) that a later form of Hebrew is in use in Isaiah 40-66, it is equally clear that the older form of Hebrew is also used. This points to later editorial use of older material written by, or recorded on behalf of, the “original” Isaiah. Such re-purposing and editing makes more sense than saying Isaiah 40-66 was composed from scratch well after Isaiah’s lifetime.

I hope that’s enough. These are the easier ones. In the next post I’ll cover a few more difficult examples.

The Naked Bible's Thoughts on Inspiration - Part 3 - The Myth of the Holy Stapler

The Naked Bible’s Thoughts on Inspiration, Part 4 – Which Edition of the Book of Joshua Originated with God but not the Human Writers?

My focus for this post is Joshua 8:30-35.

For centuries scholars have considered the placement of Joshua 8:30-35 to be a odd problem in that book. The reason is that it is completely out of place (or so it seems) with the campaigns of Joshua. In Joshua 5 the new generation of Israelites are circumcised, the Passover is celebrated, and the Jordan is crossed. The location is central Canaan for obvious reasons. God had instructed Joshua to divide and conquer. The military goal was to take the center of Canaan, cutting off north and south from each other and thus preventing a unified force from forming against the Israelite army. In Joshua 6 we read of the conquest of Jericho. Joshua 7 takes us to nearby Ai and the incident with Achan. Ai is conquered after Achan is judged in Joshua 8:1-34, bringing us to the problem section. All of a sudden, after taking two of the cities in the center of Canaan, Joshua 8:30-35 tells us that Joshua (with all the people of the nation, no less) builds an altar at Ebal and renews the covenant. Mount Ebal was the place where Moses had commanded the Israelites that they should build an altar when they entered the land.

Unless you know the geography, you don’t see the problem. The location of Mount Ebal is 70 miles from Ai/Jericho! Why on earth would Joshua march the nation 70 miles? Not only would this disrupt the entire military strategy, but it makes no sense to go to Ebal AFTER beginning the conquest, when Moses had instructed the covenant renewal when they entered the land. Now, IF this covenant ceremony had taken place in chapter 5, when the males were circumcised (which was part of the covenant!), THAT would make good sense. But it isn’t in chapter 5, it’s in 8:30-35 . . . well, at least in one version of the book of Joshua.

There are two other text versions of the book of Joshua witnessed by manuscripts at Qumran. The ceremony at Ebal is in a different place in all three versions of Joshua! In the Masoretic text (MT), which our Bibles follow, it’s at 8:30-35, which has befuddled scholars for a very long time since it makes absolutely no sense in terms of the geography and military strategy. In the Dead Sea Scroll material of Joshua, it is located just before the observances of circumcision and Passover, between 5:1 and 5:2, which makes perfect sense. In the LXX, it is found just after the notice of a Canaanite coalition that came against the Israelites, after 9:2. To be a bit more precise, I’ll cite Dave Howard’s summary:

At this juncture in the text, one of the most important divergences from the Masoretic manuscript traditions upon which our Bible translations are based is found in the Qumran scrolls. In one short fragment, portions of Josh 8:34-35 and an editorial transition not found in any other extant Bible manuscript immediately precede Josh 5:2. The portion is very fragmentary, but it is almost certain that all of 8:30-35 preceded 5:2. This shows a radically different order and arrangement from the majority Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible upon which almost all Bible translations are based today. . . . Thus, the evidence from Qumran that Joshua and the Israelites fulfilled these instructions immediately after the crossing is very important. This evidence is buttressed by Josephus’s account (the first-century Jewish historian), who mentions the building of an altar immediately after the crossing. If the original manuscripts of Joshua did have this covenant renewal ceremony between 5:1 and 5:2, then this shows the Israelites attempting to obey Moses’ commands as closely as possible. This fits in very well with the following two episodes in chap. 5: the ceremonies of circumcision and Passover. Both of these (or all three) show the continuing attention in the book’s early chapters to the command-fulfillment pattern we have observed and to the Israelites’ ritual proper preparation before they began their military encounters (NAC, Joshua, p. 145).

My purpose here is not to solve the problem. Rather, it is to point out that three separate editions of the book of Joshua were extant in the Qumran evidence. At least one scribe at Qumran felt that there was a problem in what would become known as MT – the problem of having the ceremony at 8:30-35, which makes little sense. The scribe therefore moved that material and added a few words to make the rearrangement coherent. Someone corrected someone else. In this case, the Qumran editor corrected a text tradition that we inherited.

Now, to be fair, there are scholars who argue that MT should be retained, even though it violates the geography, the divine military strategy, and (apparently) the divine command through Moses. For instance, Butler argues in the Word Biblical Commentary that the placement of the Ebal ceremony at 8:30-35 is done for theological reasons (recall the Chronicler does this sort of thing for theological purposes). Since the covenant had been violated at Ai, after Achan was judged, Joshua needed to go to Ebal and make things right. The editor of what would become MT then either deliberately fashioned his text tradition this way, or he corrected an existing text tradition that would have matched the Qumran edition.

The question is, of course, who corrected who? We can’t be selective with appeals to providence, either. Providence can work both ways. One could say, “well, MT is the right one since God preserved that in the rabbinic community” (of course we’d conveniently be forgetting that the same community preserved a text that had deliberate changes in it for arguing against points of Christian theology). Conversely, one could say (as conservative evangelicals argue every day for text critical issues) that God providentially brought the right text to light (which would be the Dead Sea version in this example) – but realize that the correction of MT would have already taken place in ancient times, likely the period after the exile when basically everyone agrees the final form of the canon was completed. Nevertheless, the separate traditions (versions) of Joshua survived in manuscript copies and libraries beyond that date.

So how does this relate to the inspiration model I’m sketching? Well, in either case (I don’t really care how the chicken or egg problem resolves), I would say that God was in the process-the correction that was needed was made (whichever direction that went – we have both, so the need to know lessens for me). There was one “correct” version that God would have approved at the end of the inspiration process. He then left if to men to copy the results. Men muddied the waters by keeping both (all three) text traditions alive. Maybe they couldn’t decide which one had emerged at the end of the inspiration process, and so they kept all three afloat rather than make the wrong choice and kill off the right tradition. We just don’t know what was in their heads on this. Maybe they didn’t care what arrangement order was right – perhaps we are unique in caring because of our modern, rational, empiricist outlook on such things in nailing down God as the source of each word while forbidding human authors as the source in any way. At any rate, since I have humans as the immediate authors and God as ultimate, providentially invested in the process, I don’t need greater certainty than what I’ve expressed. If I thought that humans were not to be seen as the originators of the Scripture in any way (if I denied anthropopneustos), then I’d feel like I needed an answer as to WHICH text originated with God and which didn’t. Since I’m not omniscient, I’d never be able to scratch that certainty itch, which would be annoying, and perhaps disturbing. But I just don’t think we need to look at things that way. My view of inspiration relieves me of the burden of pretending to have answers to such questions as knowing which one text was “the” text God (alone) originated, and – more importantly – of pretending that such questions matter. I can let God surprise me in heaven with which text was the one he wanted at the end of the inspiration process. I can say “who cares” when a critic says the biblical text existed in several versions and was edited after the exile (the oldest evidence we have). I’d EXPECT the text to get edited since that’s how books are made (and were made – see my denial of the holy stapler idea in the last post). God was in the process. We know there were rounds of editing because of the manuscript data, but we don’t know the order of the rounds. That would matter only if I denied editing happened and I needed to know the order. I don’t on both counts.

By the way – one addendum here. If one acknowledges that any editing occurred, how does the view of inspiration that denies anthropopneustos deal with it? It is one thing to say that every word originated with God and not with man and then gloss over the problems that entails in the inspiration process. It is quite another to say, on one hand, that God himself selected every word and then, on the other hand, say that some of the words were changed. If God selected every word (if he was the immediate source), then why would any correction be needed? Mind you, we’re not talking about textual transmission and manuscripts. As the last post indicated, we’re talking about (1) added explanatory notes (did God need to go back and do a better job?); (2) marks of the merging of material (cf. Ezekiel 1 and changes of person; why did God choose to vary person? If he was breathing it out and humans weren’t selecting the material, why not just stick with first or third person?); and (3) re-purposing material. We haven’t even gotten to how NT authors occasionally change the wording of verses from the OT they quote (why would God do that if HE had given the original wording – wasn’t it sufficiently clear or suited to his purpose? Wouldn’t he have known it needed changing if he selected the words in light of his own omniscience?). Isn’t just adopting something like the model I’m trying to articulate easier? Why create these theological grenades by denying the obvious place of humans as the immediate source of the text?

In the next post, I’ll hit on the granddaddy of the “more than one version” problems and then hopefully move on to quotation examples.

The Naked Bible’s Thoughts on Inspiration, Part 5 – Which Edition of the Book of Jeremiah Originated with God but not the Human Writers?

It’s been pretty quiet at The Naked Bible. The last post on the multiple editions of Joshua didn’t get much of a response. It’s made me wonder about posting more edition “problems” — especially this one — but I promised. Again, the issue of the biblical books being edited during and after the exile is not a problem with respect to the view of inspiration I’m espousing here. We have incontrovertible evidence that books were either edited well after the presumably original work was composed, or that books were put together by editors for the first time after the prophet was dead and gone — that is, his material was either written piecemeal by himself or recorded by others, and then only later fashioned into the “book” we have. I believe God was in this process and that, by providential means, his Spirit oversaw the results of what the original authors and later editors did to produce the canonical books.

We not turn to the most dramatic example of a biblical book in flux sometime between the exile and the “intertestamental” period: the book of Jeremiah. We know that those chronological boundaries are appropriate, since Jeremiah lived until shortly after the exile began, and since we have evidence for two dramatically different versions of the book at Qumran among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

There is quite a bit of difference between the Masoretic text (MT) of Jeremiah — the version our English Bibles are based on — and the Hebrew text underlying the Septuagint (LXX), the Greek translation of the OT (and so Jeremiah in this discussion), and the Bible quoted most often by the New Testament writers. The LXX of Jeremiah is about one-eighth shorter than the Masoretic text of Jeremiah. Since the book of Jeremiah is so long, this amounts to hundreds of verses and thousands of words. Additionally, the order of the chapters differs, and material within the chapters also differs in order. The following chart illustrates the chapter order divergence:

Let’s think first about the ramifications of this data. Certainly the LXX is not to be considered superior or preferable in all instances where it differs from MT. However, the remains of many Hebrew texts at Qumran agree with the Septuagint against MT. A good number of those instances also coincide with NT quotations — and so we know the NT writers used or preferred the LXX against MT in those places. In fact, many specialists estimate that roughly 3/4 of the time a NT author quoted the OT, the quotation matches or is closer to LXX than MT. All this means that we can’t just write off the LXX and say “well, we’ll just go with the MT.” Lastly, if LXX is the better version or edition, or is even better half the time, then it could be argued that the Bible used in the English (only) reading world has a lot of added material in it. In reality, though, claims like “this version or that version is THE best version” can’t be made with coherence since we aren’t omniscient. We just can’t know how the version issue (which one was the final edit) can be resolved. For evangelical scholars who have facility with Greek and Hebrew, it’s a non-issue since scholars work hard to come to their own decisions passage-by-passage as to what was most likely original. Fortunately, more recent translations are starting to go with Dead Sea Scroll and LXX readings in the running text, which helps English readers have more confidence that their translation reflects the final form of the books of the Bible. UNFORTUNATELY, though, this hasn’t been done with Jeremiah since the results would frighten uninitiated pastors and laity. So we just live with MT for completely pragmatic reasons.

Before concluding, I should note that it isn’t only Jeremiah and Joshua that differ in order of material and significant amount of content. There are other books where evidence of more than one version exists. For instance, LXX Job is about one-sixth smaller than MT Job, and includes an ending not extant in MT Hebrew, and almost half of the verses in LXX Esther are not found in MT Esther.

This is the kind of “real world” data that “God alone” statements of inspiration ignore. There is no sense in denying anthropopneustos, and it seems dishonest to do so with respect to such data. Having humans as the immediate but not ultimate source of the biblical text is far more coherent; it gives pride of place to theopneustos without denying reality or claiming omniscience. This is why I think it nonsensical to ignore the data in favor of something like the Westminster Confession. Confessions are worthwhile, but they are historically circumscribed. I’m no expert in LXX studies, but I’m guessing the authors of the Confession may not have known much about these issues, or even the LXX. The LXX was certainly known in antiquity, but the loss of Greek in Europe in all but the monasteries until the Renaissance may have meant that few scholars before the 19th century did much work in LXX. I’m not an LXX expert, so I don’t know. Whether they didn’t know or didn’t care, it’s hard for me to understand how we should care more about how a 17th century Confession articulates inspiration than how contemporary scholars equally committed to inspiration would handle the issue.

1 Samuel 13:1 – The Matter of Missing Words in the Bible

1 Samuel 13:1 is sort of a classic OT textual criticism problem. The United Bible Society’s Handbook for Translators of 1 Samuel describes the problem this way:1

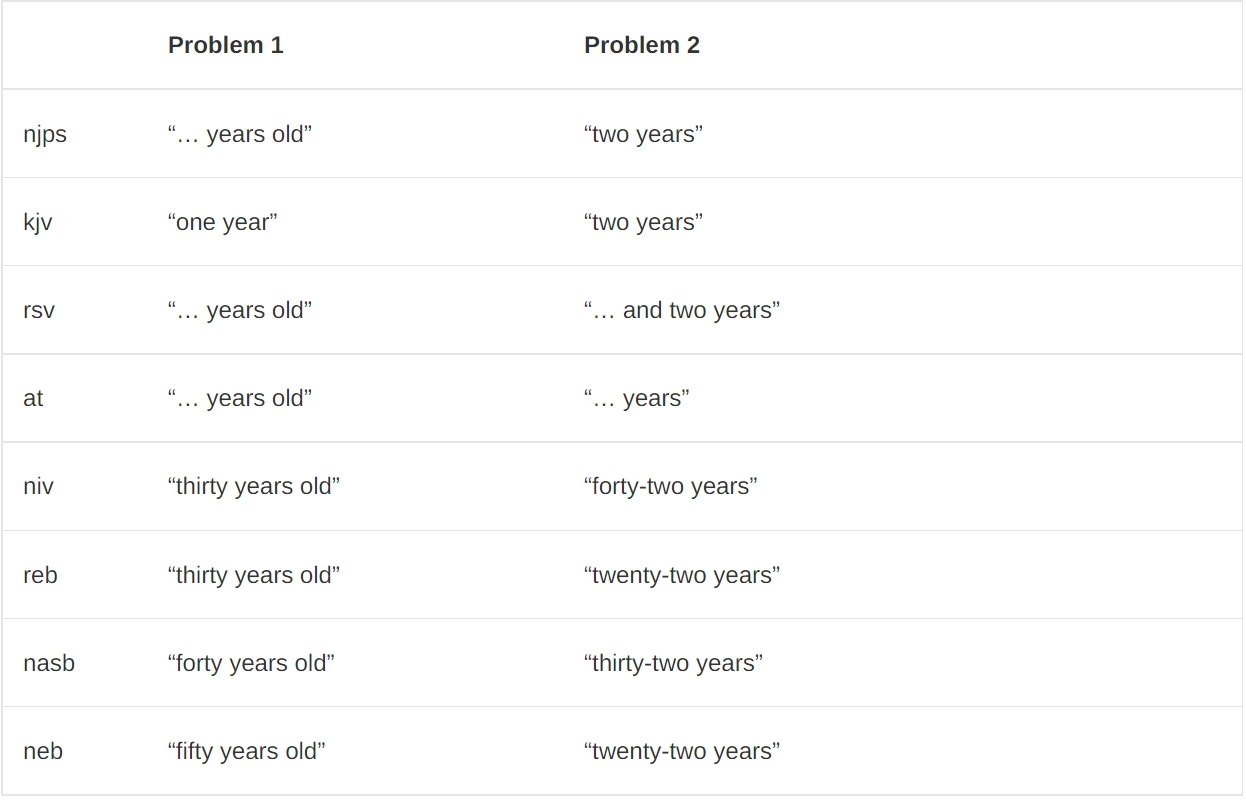

This verse follows the standard formula for introducing kings of Israel (and later also of Judah) in the books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles. But this verse contains one of the most difficult textual problems in the book of 1 Samuel, if not of the whole Bible. The following table shows the great diversity of solutions to the problems:

The Masoretic Text (MT) literally says “Saul was a son of a year in his reigning and two years he reigned over Israel.” Obviously there are two errors in the Hebrew text as we have it today: (1) Saul was not one year old when he became king, and (2) he reigned more than two years.

The first error is obvious, since the book of 1 Samuel tells us plainly how Saul was chosen and anointed king — and he was a full grown man. The second error is plain when viewed against Acts 13:21 (and when reading the account of Saul’s kingship in the OT).

Now, in one regard, this is no different than any other text-critical problem. You detect the error in the present text, then work to find out how it came about, and consult other manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible for the solution. But there’s the rub — in the case of 1 Sam 13:1, there are no other reliable manuscript readings.

Interpreters and translators have followed many solutions to this textual problem (and note that the choice of solution for “problem 1” gives rise to the reading of “problem 2”). Quoting from the UBS Handbook again:

(a) Some translations, following the example of the Septuagint, omit the entire verse (so tev, frcl, and itcl).

(b) Some translate the verse but leave blank spaces as in rsv (so also nrsv, nab, Osty, and bp).

(c) Others leave only the first number blank.

(d) Some follow the first-century Jewish historian Josephus and Acts 13.21, and claim that Saul ruled for (about) forty years. Compare niv “Saul was thirty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel forty-two years.” The “thirty years” is based on a few late Septuagint manuscripts.

Solution (d) above may seem the best at first glance, but a major problem with this is that early in his rule Saul already has a grown son able to command troops (see verse 2). Therefore Saul must have been older than thirty when he became king.

Note well the comments about solution “d” – the only reason some versions read “thirty” in the verse is because the number is found in a few LATE manuscripts of the LXX. But that number cannot be right. Where does “thirty” come from in those few manuscripts? The textual note on the verse in the Word Biblical Commentary summarizes the answer nicely:

A few LXX mss, have “thirty,” though this seems to be a secondary calculation (cf. 2 Sam 5:4). Since Jonathan was old enough to have 1,000 troops under his command in v 2, and since Saul had a grandson before his death (2 Sam 4:4), an age of forty or more is plausible. The whole verse is lacking in most LXX mss.

The “thirty” was simply borrowed by some LXX scribe from 2 Sam 5:4, which is talking about DAVID! They were confused by the error, and that was their solution!

The textual reality, as it stands today, is that the number is lost. We just don’t have any manuscript evidence for a coherent reading.

For our purposes, in my mind this is the same sort of issue as I’ve just covered in regard to Joshua 8:30-35 and Jeremiah. I’d approach it the same way with respect to inspiration. There *was* some thing produced by the process of inspiration, where men were the immediate source of the text, and God was the ultimate source. When that *produced thing* was finished, I believe the text was whole (that there WAS a coherent reading in 1 Samuel 13:1). Since that time, transmission of the text was left to human beings, and now we have a missing word or words.

What’s the point? Only to note two things:

(1) like traditional articulations of inspiration, I believe that inspiration does not apply to copying the final product. There is no guarantee from God in the Bible that transmission of the text would be inerrant. Our copies of the Scripture (one the simplest level) are “inerrant” when they reflect the contents of the original thing produced. Of course, we’ve spent weeks on this blog already dealing with the reality that inerrancy concerns a lot more than this issue (and I promise we’ll get back to those things). in 1 Samuel 13:1, then, our Bible is “errant” in that something is missing, but NOT in the sense that the original thing produced by inspiration was wrong. The original product of inspiration was whole. Perhaps (like the historical problems readers have brought up) we will find manuscript evidence for 1 Sam 13:1. That would be cool. But until then, I believe it is philosophically and theologically coherent to stick with a process of inspiration that produced a whole product that was inerrant.

(2) An example like this helps us to factor in yet another facet of what we actually find in the biblical text. When we get back to inerrancy, we’ll have to return here and pick this up as part of trying to find a definition that works.

Omanson, R. L., & Ellington, J. (2001). A handbook on the first book of Samuel. UBS handbook series (252). New York: United Bible Societies.

Klein, R. W. (2002). Vol. 10: Word Biblical Commentary : 1 Samuel. Word Biblical Commentary (122). Dallas: Word, Incorporated.

1 Samuel 13:1 – The Matter of Missing Words in the Bible

Inspiration and Inerrancy: Distinguishing Ends and Means, Process and Product

In the last post, I focused on 2 Tim 3:17 for an answer to the question, “What was the point of the exercise of inspiration?” Paul gives us four purposes in this text, and it seems wise to me to approach the question from that perspective. I also noted that I have no interest in affirming “limited inerrancy.” All well and good, but I also think we need to let Scripture tell us what Scripture was intended for and not try to articulate what we believe about Scripture on some other basis – like our need as moderns of Enlightenment thinking to cram everything in a box or neat categories so we can pretend that all the problems are solved and all the questions have real time (OUR time) answers. So where’s the middle ground? I’m going to try and find that middle ground and then steer through it. I’d really like some critical input here, since I’m making this up as I go.

I’ll start with an analogy. (My apologies for the way TABLES do NOT work well in WordPress).

Evangelicals know that this looks like a completely human process of recognition, but we believe God was in the process, “superintending” the decisions made by humans. Hence we assign the results to providence. As readers know, I have argued inspiration should be viewed the same way. Just as no one would argue God whispered which books were “in” to those people debating such a thing, we do not need God to whisper each word into the ear or mind of the Scripture authors. There is no need for dictation or automatic writing, any more than there was a need to dictate the canon list or seize the minds of those making such decisions. It was providence.

The next obvious question is “How well did the process work?” This is another way of asking whether God preserved the human agents from making any mistakes. In the case of the canon, mistakes would mean not recognizing a book that ought to have been recognized. I exclude the notion in that statement that something got in that shouldn’t be in. That is theoretically possible, but in my mind highly unlikely, especially for the Protestant evangelicals that I’m guessing make up most or all of my readership. Evangelicalism has a minimalist canon – the smallest of the lists that emerged in any widespread Christian tradition, so the problem becomes whether something that ought to be in was excluded in what has become the evangelical Protestant Bible. Moving back to the inspiration issue, mistakes would mean errors in the text. This brings us full circle back to 2 Tim. 3:17.

We all know that human agents (whether as part of the inspiration process or the canon recognition process) are fallible. We would all agree that God could overcome such frailty if he chose to do so.

God would only approve what was consistent with his own purposes. If something in the text obstructed or obscured his purposes, he would not have allowed it. I am suggesting as a general principle that THIS PERSPECTIVE ought to be the guiding criterion for whether the Bible has errant content in it.

How does this differ from limited inerrancy? I’ll try to illustrate that – but be advised, I need input on better ways to say things here since I’m making this up!

Now here’s my problem. I know that this sounds like I’m just saying certain things don’t count when it comes to inerrancy. And, that’s sort of in my ballpark. But what I’m really saying is “that’s fair to say” since I think we ought to play by Scripture’s own rules – it tells us what it’s for. We ought not to judge Scripture’s errancy by standards that are well outside its own context and purposes.

We cut written and spoken material this kind of slack all the time. We know intuitively in many cases *how* a certain statement was intended to be taken (“Since the sun rises every day the way God made it to, we can believe God is faithful”). A scientifically imprecise thing to say, but it wasn’t my intent to lay down scientific fact. My point was the latter truth that extended from my colloquialism. The problem is with US – we often don’t know how a certain statement ought to be taken. And when we do know that, for example, the real point wasn’t to give us science, why not cut the Bible the same slack?1 Well, you might say, “we can’t cut it slack, since it was written by God, and he ought to know better.” Sorry – it wasn’t written by God. God was not the immediate author – the people he chose to produce it were. It is God’s thoughts in human words, and very focused, pared-down divine thoughts at that, for our sake. Let’s face it – once God made the decision to use people to produce Scripture rather than dictate content to us that would have been mostly incomprehensible to our puny minds, he had chosen a very limited resource. I imagine God looking down and shaking his head as it were, knowing the only way to communicate with us would be to use us to that end. God had specific purposes in mind and more or less said “Well, I’ll prompt them with my Spirit, other believers, and general providential intervention to get them to write down a record of my dealings with humanity, my purposes, who I am and what I’m like, how they can know me and be forgiven for their sin, how I came to them in human form and then the incarnate Son. . .” etc., etc. “I’ll make sure they get across what I want them to get across, not only for them but for all those who will follow, especially those who believe.” God knew that letting men do this would be ugly (relatively speaking, with respect to his perfection) – that they’d bring their pre-scientific ignorance to the table, along with a specific, localized cultural perspective. But hey, that’s what he chose to work with. What else would they be?